"Overruling all seeming evil for our greater good"

Willard Richard's April 6, 1852 Dedicatory Prayer of the New Tabernacle

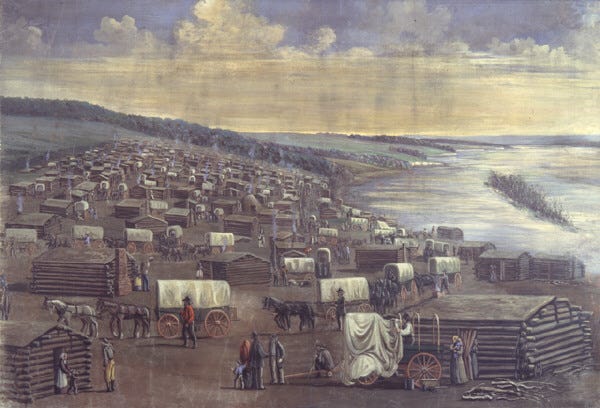

April 6, 1852. Along what were likely muddy roads due to melting snow and occasional rain showers, thousands of people made their way towards the settlement of Salt Lake City, the heart of the Latter-day Saint Great Basin home that sat in the shadows of the Wasatch Front.1 Only five years removed from their initial entrance into the Salt Lake Valley, there were already over 11,000 settlers in Utah Territory, the vast majority living between Salt Lake City and Provo.2

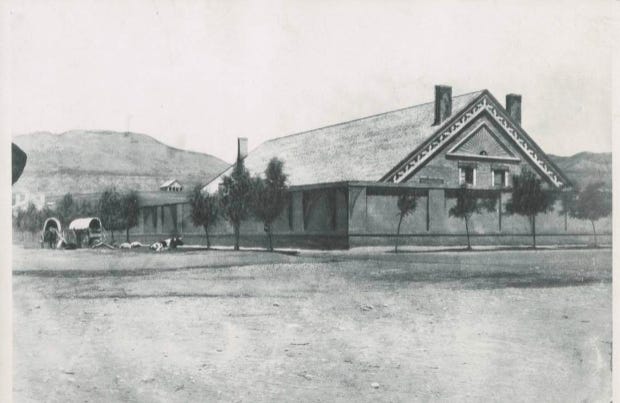

They gathered to participate in the Church’s general conference, which was to be held in the newly constructed “New Tabernacle.” Previously, the Saints had gathered in covered shelters called boweries (due to their roofs being made out of branches) which could hold up to a thousand people at once. However, these temporary structures were open to the unpredictable weather of the Rocky Mountains. Church leaders had long planned for a more permanent structure to replace the boweries and in May 1851 the Saints during the general conference had approved the construction of a adobe tabernacle to be completed by the Public Works department of the Church.3 Over the next several months hundreds of men were paid in cash and food as they worked on building the one hundred and twenty foot by sixty foot wide structure in the southwestern portion of Temple Square.4

The work on the tabernacle was finished only several weeks prior to the Church’s general conference. Built of adobe and with elements of Greek revival architecture, the new building could hold over 2,000 participants. Built half below ground and with a sloped floor, the tabernacle provided an excellent auditorium that allowed all congregants to see and hear the speakers. Excitement was palpable among a people with little material wealth to have completed such a building. While many other western settlements remained rough and transient, particularly as legions of gold seekers continued to flood the West in the wake of California Gold Rush, Latter-day Saints had built edifices to promote worship and to gather together as friends, families, and fellow believers. While other communities were focused on extracting materials to ship to the East, Latter-day Saints sought to build a community that was more than a colonial outpost of the United States. They sought to build a Zion centered community, one where the welfare of all mattered more than the individual riches of the individual.5

Wilford Woodruff wrote in his diary, “The Tabernacle was filled to overflowing in an hour after the doors were open & hundreds could not get into the house.” Over the next few days every meeting in the “New Tabernacle” was packed to the brim, with men standing in the aisles to allow women and children seating.6 The energy in the building was palpable, with Brigham Young three days later commenting to the assembled Saints that the meetings of this conference had the potential to become as impactful as that of the biblical Day of Pentecost.7

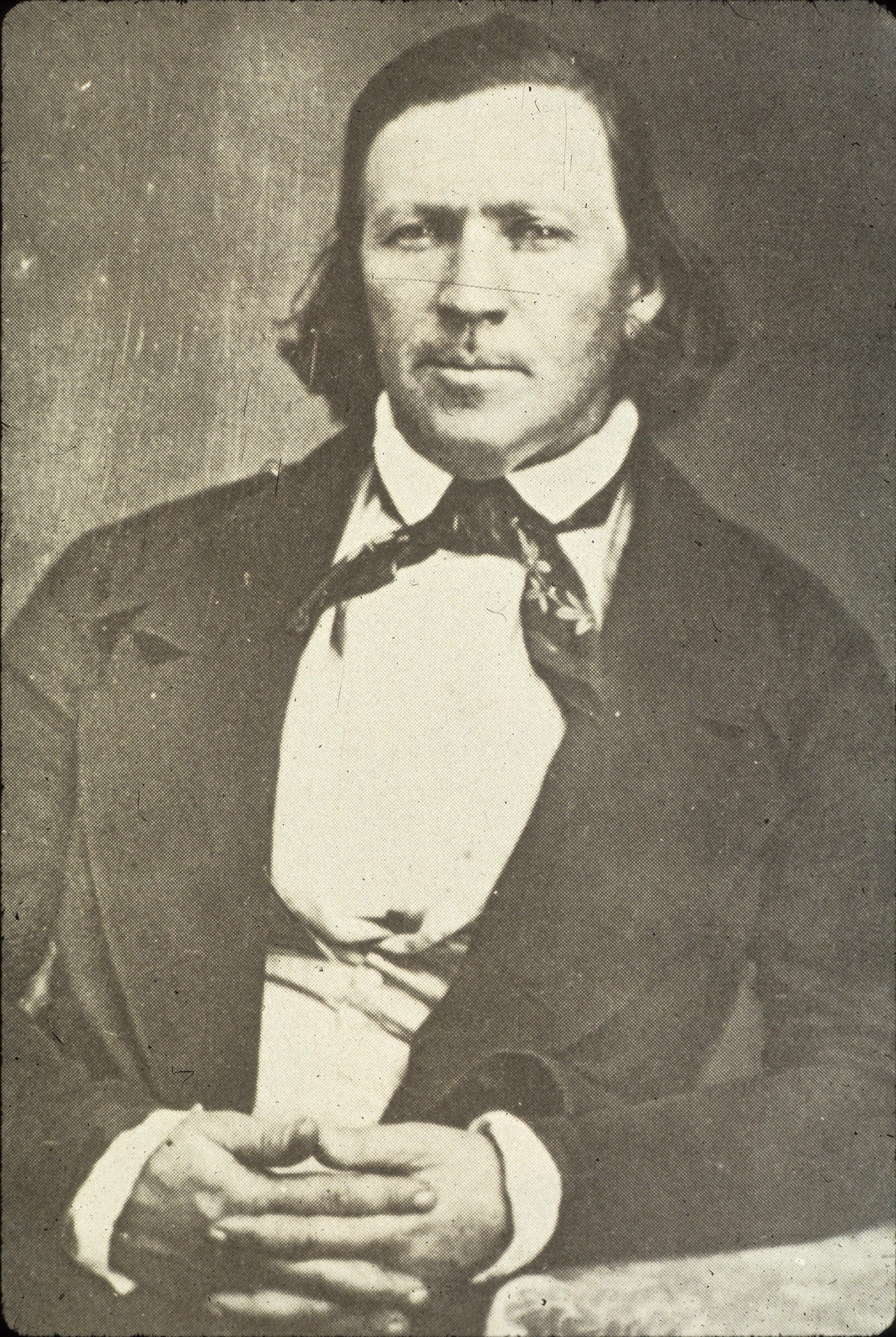

Soon after the some 2000 Saints had found seats or spots to stand at 10 a.m., Brigham Young, the President and Prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, complimented the Saints on how quickly they had raised the new edifice. For someone who had worked for almost three years on the 15,000 sq. foot Kirtland Temple, to see the Saints build a tabernacle of over 7,000 sq. feet in less than a year, must have energized the 50 year old prophet and seer. Young read the favorite Latter-day Saint hymn, “The Morning Breaks the Shadows Flee,” which was then sung by the choir. Following singing, Willard Richards, the forty-eight year old apostle known to the Saints as Dr. Richards, stood to give the dedicatory prayer.

Willard Richards was born in Hopkin, Massachusetts. He was briefly a school teacher and a Thomsonian doctor.8 An early convert to the Church and a cousin of Brigham Young, Richards was appointed an Apostle on April 14, 1840. When Brigham Young was sustained as the president of the Church in December of 1847, Richards, while still serving as Church historian, was called to serve as a Second Counselor in the newly reconstituted First Presidency.

As Richard’s dedicated the tabernacle, he poured his heart out to God, pleading with the Lord to help and bless the Saints. This prayer follows similar patterns of other dedicatory Latter-day Saint prayers. God was petitioned to bless "this house as a holy sanctuary,” to bless the structural elements including the floors, the doors, the roof, the beams, and the walls. This essay approaches Richards’ prayer as a sincere effort to commune with the Divine, rather than a performative display for those gathered in the tabernacle. It was an effort to convey Richards’, as well as the assembled Saints’, faith and hopes to heaven, where they were confident their loving Heavenly Father listened.

Religion, contrary to some historians’ views, is more than just a cover for economic leveraging and oppressing of those around oneself. Religious belief is more than just intellectual knowledge, but taps into some of the most central emotions that drive mankind: faith, hope, fear, sorrow, and love. For many in human history, it is an all encompassing aspect of lived experience that impacts and dictates other aspects of life. Richards, a man who spent most of his life in the service of Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, is one example. This faith was not one born of luxury or opulence. Rather, one can clearly see the fires of faith that motivated him to forsake all and remain with the Saints as he suffered and was persecuted for his beliefs.

Dedicatory prayers can at times seem mundane, or offer little for additional comment. However, I suggest that this prayer reflects some of the most important fears, hopes, and aspirations of the Latter-day Saints community in 1852. Richards sought to be the voice for the congregation, to channel their fears and solutions rested in faith highlighting a deep and enduring optimism in the future and destiny of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Perhaps seen as diametrically opposed, it was the interplay of fear and faith that led Richard’s to have hope in the future. It will not cover every aspect of the dedication, but rather center on several parts that highlight Latter-day Saint fears and faith filled solutions.

Richard’s began by addressing “Great and all-wise God, our Heavenly Father, who dwellest amid the cherubim, and art clothed with light as with a garment” in the name of Jesus Christ and “by virtue of the Holy and Eternal Priesthood.” These opening lines connect to some of the deepest theological ideas, for example the centrality of Jesus Christ and his mediation between mankind and the Father. It also demonstrates how Latter-day Saints viewed the priesthood, the permission to act in God’s name for the benefit of His children, as central to any actions they did, including dedicating a tabernacle. To Richards and those assembled, they believed that those who accepted the Latter-day Saint message were incorporated into the timeless House of Israel, becoming disciples of Christ and builders of a modern Zion. Through it all, they believed that God the Father was the strength behind their efforts, transforming weak, mortal acts into eternity shaping efforts.9

Continuing, he pled for “thy spirit upon each and every soul now waiting before thee, that our hearts may be united as one.” Latter-day Saints had long been concerned with creating a united community, in part to complete with the Lord’s command given in a 1831 revelation from Jesus Christ to the Prophet Joseph, “I say unto you, be one; and if ye are not one ye are not mine.”10 Often articulated as building Zion (a reference to a society similar to the City of Enoch, a society that were “of one heart and one mind, and dwelt in righteousness; and there was no poor among them.”), this preoccupation with unity remained a constant theme both in religious and economic projects undertaken by the Saints, such as the co-operative movement, the United Order, and the current system of tithes and offerings. It reflects both fear and the counterbalancing faith. Fear of not doing enough, of the community still being mired in the spiritual quicksand of “Babylon,” of being too self-centered, proud, and contentious to receive the blessings of heaven. But also faith that through Christ and His mercy something more could be created out of halting and slow efforts of mortal beings.11

Shifting his focus, Richard’s expressed gratitude for the revelations given to Joseph Smith and the Saints’ deliverance “from the power of Satan and the devices and machinations of wicked and designing men, who have sought our overthrow and conspired against our lives.” It is in this line, that one can note one of the Saints’ fears of this period. Richards and many of those gathered at the Tabernacle had first hand experience with “mobbers, and murderers,” as they had been driven out of Missouri and Illinois at gun point. Furthermore, many of those from Great Britain and Europe had also seen acts of violence against missionaries and members in their homelands. It was not far from their minds of what could be if their fellow Americans decided the “Mormon Problem” needed to be resolved.

It can be underappreciated by those who have not lived through Antebellum mob violence how much the security of Rocky Mountain isolation brought the 19th century Saints. It is important to note that many Latter-day Saints believed things could have gotten much worse. While some may scoff as such a belief, rumor and the inflammatory rhetoric found in newspapers throughout the United States and Europe painted a picture of a world deeply hostile to the Saints. As with other minority groups in the United States, the Saints understood that tensions could explode and result in far worse than they had experienced.12 Richards noted that many Saints “have fallen by mobocracy, violence, disease, and death, and their bones have been left to moolder upon the prairie and in the wilderness.”

He and other Saints saw the violence of “mobocracy” continuing beyond simple expulsion. The majority of the deaths in the exodus he felt were as attributable to the mobs, who had refused to let the Saints remain in their homes until a western haven had been built, as to trail realities. This extended view of mob violence passes current depictions that terminate mob effects when Saints leave a site of persecution, a helpful reminder that to those living, the effects were not localized or merely momentary. The graveyards along the Missouri River and the markers along the trails only reminded the Saints the cost of discipleship in 19th century America.13

Yet, Richards and other Saints approached this fear with a faith-filled view of the past, believing that through it all that God was merciful and “hast ever been mindful of us, overruling all seeming evil for our greater good, until by thy mighty power thou hast brought us to a glorious inheritance in this goodly land, choice above all other lands.” In this regard, Richards emphasized the Saints’ belief in agency and the intervention of the divine in human affairs (known academically as providentialism). Neither the persecutors nor the victims were destined to clash. Instead, the persecutors had used their agency (or freedom to act for themselves) to attack and drive out the Saints. However, Richard’s was clear that he believed it was only through the intervention of the divine that the Saints had escaped with their lives. Richards himself experienced this personally as he was in the jail cell where Hyrum and Joseph Smith were murdered by a mob, yet he escaped with no injuries, something he believed was a result of the intervention of God. Richards made no attempt to solve the question of why God intervenes in some cases but not others in this prayer. He simply acknowledged a truth he knew; that God had been with the Saints and preserved many of them from destruction. This did not remove the sorrow of lost friends whose “blood yet cries from the ground for vengeance to be poured out from the Heavens,” yet Richards and others took comfort in the timing of God’s will and in His mercy.

As Richards proceeded to dedicate the building, he blessed all parts of the structure, throughout it emphasizing that the building might become “holy.” In the 1828 Webster’s Dictionary, “Holy” was defined as

1. Properly, whole, entire or perfect, in a moral sense. Hence, pure in heart, temper or dispositions; free from sin and sinful affections. Applied to the Supreme Being, holy signifies perfectly pure, immaculate and complete in moral character; and man is more or less holy as his heart is more or less sanctified, or purified from evil dispositions. We call a man holy when his heart is conformed in some degree to the image of God, and his life is regulated by the divine precepts. Hence, holy is used as nearly synonymous with good, pious, godly.

2. Hallowed; consecrated or set apart to a sacred use, or to the service or worship of God; a sense frequent in Scripture; as the holy sabbath; holy oil; holy vessels; a holy nation; the holy temple; a holy priesthood.14

Richards clearly had both definitions in mind as he interconnected the concept of sacred structure allowing for sacred personal transformation.

As with the first part of his prayer, Richards returned again to confront the fear of his people insufficiently transforming themselves into Saints of the Most High God. He hoped the Saints could listen and learn in the New Tabernacle, deepening their conversion to Jesus Christ and His Gospel. Richards also hoped that the structure could be a place where “angels,” as well as the Holy Ghost, could minister to the Saints and feed them as “manna from heaven” leading the Saints to be symbolically “clothed in robes of righteousness.” He further hoped this transformation could lead the Saints to having “the visions and revelations of the eternal worlds be open before them continually.” Rather than relegate heavenly manifestations to the days of Brother Joseph, Richards anticipated that such miracles as seen in Kirtland and Nauvoo, would continue in the Saints’ Rocky Mountain haven.

He further asked that those not of the faith, particularly the “honest in heart” feel the power of God within the walls. While certainly the Saints could be seen as exclusionary in their rhetoric of “Gentiles” and “Saints” (in part a reaction to their fears of mob violence) it is important to note that even in the early years of settlement in Utah Territory, Latter-day Saints welcomed outsiders, particularly those who manifested a willingness to understand, rather than persecute the Saints. At times, this has been overlooked in historical narratives that frame Utah as an hostile place. Yet, this fails to recognize that many who claimed Utah to be exclusionary were part of efforts to curtail and even subject the Latter-day Saints to an American pan-Protestant hegemony, just as was happening with Catholics and Native Americans. Allies of the Saints or those who were neutral were often complimentary of the Saints and the world they were building in Utah, despite frequently disagreeing with their religious practices, primarily polygamy. Richards plea reflected faith in the face of fear of outside hostility, a flame of faith that good people existed and would have mercy on the Saints, even if they did not .15

Richards then began asking blessings on various groups and individuals.16 After praying for the Saints and the religious leadership of the Church, he made an explicit turn to those in secular positions, as well as those outside the Church. Richards prayed for the Governor (Brigham Young), “with the Legislators, Judges, and Marshals, and Sheriffs, and all in authority among the people,” highlighting that though most of these political leadership roles were filled by those in Church leadership, the Saints still viewed the two as separate offices.17 It is at this point that Richards turned from Utah Territory and began praying for national leaders and the United States. The Saints were then well aware of the threats emanating from the East, particularly following the ruckus caused by the arrival of the “runaway” officials, a group of non-Latter-day Saint federal officials who refused to live in Utah and had returned to Washington D.C. with false allegations of the Saints building an anti-American/anti-democratic society. These accusations were not only false, but dangerous, especially if the American public and Congressional leaders decided to “put down” the Saints. It is within this context of uncertainty and fear that Richard’s words take greater meaning.

When Richards prayed for John M. Bernhisel, the Territorial delegate for Utah, he pled that he:

Be clothed upon with the spirit and power of Elijah’s God, that he may put to silence the tongues of evil men, may all the enemies of our God be confounded before him; may the wisdom of heaven be his, to lead and guide him in every emergency; and may he never be cofounded, or put to silence or fear; but may he feel that God is with him, and that he will bring him off conqueror over every foe, and stand forth triumphant in the midst of the nation, clothed with the principles of eternal truth and rectitude; and may his daily walk be an example to the world, and all with whom he associates; proving himself a friend of God, and a man after his own heart, seeking diligently to know thy mind and will, and yielding humble obedience thereunto.

Richards framing of Bernhisel as an Elijah is poignant, as Elijah was tasked with ministering to an violent and wicked Kingdom of Israel during the reign of Ahab and Jezebel.18 Latter-day Saints needed Bernhisel to work miracles by turning the tides of a largely hostile American republic, which had many citizens who celebrated the murder of Joseph Smith, many who excused mobbings and extermination orders, and who had ignored the Saints’ pleas for justice. Furthermore, many were coming to view the Saints as outsiders and threats, with some even beginning to see the Saints as sub-human.19 Richards, like other leaders in the Church of this period, turned to the Old Testament as they sought to create their own modern Israel in the face of hostile, violent opposition. Once again, the tension of fear of mobocracy and faith in divine intervention found their way into Richard’s prayer.

He also beseeched God to bless the “President of the United States,” the “heads of departments,” “for the members of Congress,” and “all those in authority over us.” Richards could have prayed for justice, for freedom from the American republic which had all too often turned its backs on the Saints during the past twenty years. Instead, he asked that the leaders have “wisdom to discern the times and administer in righteousness in their respective callings.” He asked they could “love mercy, deal justly, and seek knowledge, wisdom and judgement from him whose right it is to rule, and become subservient to his holy teachings.” The Saints still held to the belief in being “subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates,” and had accepted outsiders appointed to rule over them in federal offices. Latter-day Saints could and did speak harshly of the American public and its leaders, their critiques similar to those of other minorities who faced persecution. Yet, they still prayed for those who were all to often their enemies, hoping that “the good influences of thy Spirit control them in all their acts towards thy people, and towards all the people over whom they preside.” The Saints did not need full support, just mercy and protection to live as they saw fit.

As Richard’s wound down his prayer, he petitioned for international leaders and governments, asking that doors could be opened for the spreading of the gospel. This highlights one of the central focuses of the Latter-day Saints, to share their faith with those around them. Richards petitioned for the “overthrow all thrones, dominions, principalities, powers, and governments, that fight against thy cause and thy servants.” Important to note is that Richards did not, unlike other Americans who viewed republicanism as the only correct form of government, pray for a world filled with republics. Instead, he emphasized the justness of a government being centered on its willingness to allow freedom of religion. Rather than hoping for a global shift to republics (as envisioned by many Antebellum Americans) or democracy (as has been seen in mid-20th and early 21st century America), Richard’s saw religious freedom and freedom of conscience as the signs of just government, a departure from the broader world he came of age in.

His pleas were not confined only to governments, but he also asked that the “gospel of salvation” could flow to “all nations, kindreds, tongues, and people that dwell upon the face of the earth.” Even though many Latter-day Saints struggled with abandoning racial stereotypes common among nineteenth century Americans and Europeans, it is important to note that Richard’s and other Latter-day Saint leaders’ rhetoric emphasized a global human brotherhood and their intention to spread the gospel of Christ to all nations of the earth. There were no subdivisions of the human family, no sub-human groupings that had become common in the Western world by the mid 19th century. Living up to these beliefs, and fully accepting them, often proved a challenge, but it was still at the heart of Latter-day Saint theology of a global human family.20

As he finished his prayer, Richards turned his prayer to those he considered the direct descendants of ancient Israel, the Jews and Native Americans. For the Jews, he asked that they could return “to receive their promised inheritance and be gathered from among all nations.” Only a few years earlier, apostle Orson Hyde had dedicated the Holy Land for the return of the Jewish people. This prayer reflected Latter-day Saint belief in ancient prophecy and its connection to the present. Though Jewish gathering to the Holy Land would not begin in earnest until the late nineteenth century, the Saints believed that the prophecies of old were not just expressions of hope, but of divine will as God prepared the world for the Second Coming of the Savior.

Richards then turned to those he believed were part of the ancient lost tribes of Israel, the Native peoples. As taught in the Book of Mormon, Latter-day Saints viewed Native peoples as literal Israelites, whose ancestors had escaped Jerusalem prior to the destruction by the Babylonians in 600 B.C.21 However, Richards combined Latter-day Saints’ view that Native peoples had apostatized from the true gospel of Jesus Christ and fallen into a dark apostacy around 400 A.D, with contemporary American’s view that Native peoples were “ignorant, degraded, and [in a] miserable condition.” It is important to note, that Richards felt that sharing the gospel was not taking away from Native culture, but rather returning Native peoples to the ways of “which their fathers knew and loved.” Richards prayed emphatically that God would be “merciful unto them” and that the promises to the ancestors of the Native Americans would be fulfilled. To break the bands of “darkness, superstition, and ignorance” Richards believed the Lord would instruct them through “dreams, and visions, and revelations by thy Spirit, that they may see their degraded condition.” Richards expressed his faith that Native peoples would receive an outpouring of blessings upon accepting the gospel. Rather than focus on “civilization,” in other words of Western-Euro-American culture, Richards emphasized that Native peoples would be “enlightened in principle, in doctrine, in duty, and learn the way of life and salvation.”

In closing, Richards pled for peace, and that “thy good Spirit may be poured out upon us.” His final lines reflecting the ultimate hope Latter-day Saints held then, and still today, that they could “be enabled to accomplish thy righteous will in all things, and grow up in perfection, through the gift of thy Spirit, that at last we may rest in thy presence with all thy sanctified ones.”

This culminating sentiment, that God would help them become the type of people they hoped to be, can be seen throughout his prayer and was how Richards balanced fear and faith. He could acknowledge concerns and fears through his petitions for help and aid. He could note the realities that surrounded them (such as hostility from Native peoples and federal officials) while also trusting that the promises of God would be fulfilled regarding the Church’s and world’s destiny. He could plead for help from heaven so that he and those around him could change and build the Zion they believed could be built in the build up to the Return of Jesus Christ. He was optimistic for the future. Could Richards have conceived of the explosive growth in the late 20th and early 19th century? Could he have envisioned the construction of hundreds of sacred temples, when in 1852 the Saints could barely get the foundation of the temple laid? Perhaps so, or perhaps not. Regardless, his optimistic view of the future provided an excellent beginning to a series of meeting full of joy. For readers today, Richard’s prayer offers a glimpse into Latter-day Saint fear and faith, and how they came to an optimistic view of the future.

I will extensively use the Church History Topics essays throughout this essay as links in the text for various topics. Having worked on several of these essays, I can note that these essays are heavily vetted and pass through an extensive peer review process that few other academic publications pass through. The Though not perfect, they represent a sincere and diligent effort of Latter-day Saint scholars employed by the Church History Department of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to write faithful and accurate historical context essays that are helpful for non-academic audiences to learn more about various topics.

“Population of Utah Counties….,” U.S. Census Bulletin 30 (1901), 1.

Scott C. Esplin, The Tabernacle: An Old and Wonderful Friend (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2007), 107-136; Ronald G. Watt, Public Work Account Books Index (Salt Lake City, UT: Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1997)

Ronald H. Walker, “The Salt Lake Tabernacle in the Nineteenth Century: A Glimpse of Early Mormonism,” Journal of Mormon History 31, no. 2 (Fall 2005), 198-240; Ryan J. Hallstrom, “The Bowery and the Old Adobe Tabernacle,” Intermountain Histories (Sep. 24, 2020). This is where the Assembly Hall now stands.

Leonard Arrington, one of the foremost economic historians of the Latter-day Saints wrote several works that are useful in understanding Latter-day Saint efforts to build a Zion like world. See one example: Leonard Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-Day Saints, 1830–1900 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1958). Though much needs to be modified and rethought, Arrington was correct to note Latter-day Saint leaderships’ emphasis on building Zion as foremost in their migration west.

Historical Department Journal History of the Church, April 7, 1852, 1852 January-June, Church History Department, SLC, UT.

Historical Department Journal History of the Church, April 9, 1852, 1852 January-June, Church History Department, SLC, UT.

The Thomsonian system was an herbal medicine regime that sought to move away from then current harsh medical practices. For more on Richards see: 5. H. Dean Garrett, “Richards, Willard,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allen Kent Powell (Salt Lake City, UT: University of Utah Press, 1994) and Interview Alex Smith by Kurt Manwaring, “Who Was Willard Richards,” FromtheDesk (Apr. 25, 2024).

Richards’ opening lines also point to how the Saints viewed the supremacy of God the Father, and his role as a Father to all mankind. This divine fatherhood, taught throughout Latter-day Saint scriptural canon, as well as by the teachings of Joseph Smith and other early Church leaders, had imbedded in the Latter-day Saint world an image of a just and merciful Father, a separate being from Jesus Christ, who is all knowing, all powerful, and full of light.

See: Skinner, Andrew C., “The Doctrine of God the Father in the Book of Mormon” in A Book of Mormon Treasury: Gospel Insights from General Authorities and Religious Educators, (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2003), 412–26; James B. Allen and John W. Welch, “The Appearance of the Father and the Son to Joseph Smith in 1820,” in Exploring the First Vision, ed. Samuel Alonzo Dodge and Steven C. Harper (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 41–89; “Father in Heaven,” Guide to the Scriptures (Salt Lake City, UT: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2013). For current Latter-day Saint doctrine on God the Father see: “God the Father” Topics & Questions, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (acc. 10-19-2025), here.

This imagery of God “clothed with light” perhaps hearkens back to Doctrine and Covenants 88, a revelation shared by the prophet Joseph Smith in December of 1832. In this revelation Joseph Smith declared, “Which light proceedeth forth from the presence of God to fill immensity of space.” In a May 1833 revelation this imagery was further expanded, “He that keepeth his [God’s] commandments receiveth truth and light, until he is glorified in truth and knoweth all things….Intelligence, or the light of truth, was not created or made neither indeed can be.” (Doctrine and Covenants 93:28-29)

This idea that truth, intelligence, and light are interconnected illustrates light as being more than an adjective in Latter-day Saint theology, but a way in which to convey their belief in God the Father was full of truth and intelligence, an idea further conveyed in Joseph Smith’s landmark “King Follett” discourse.

See: “King Follett Discourse,” Church History Topics (acc. 10-19-2025), here. For the full text of the discourse see: “The King Follett Sermon,” Ensign (Apr. 1971), here. For additional context in regards to the King Follett sermon see: “Accounts of the ‘King Follett Sermon,’” The Joseph Smith Papers (acc. 10-19-2025), here.

For a fascinating book on the United Order, see Leonard Arrington, Feramorz Y. Fox, and Dean L. May, Building the City of God: Community and Cooperation Among the Mormons (University of Illinois Press, 1992)

One need only look at Antebellum anti-Black violence, anti-Catholic violence, and anti-Asian violence to see how things could get worse.

Two books come to mind discussing this era of violence: David Grimsted, American Mobbing, 1828-1861: Toward Civil War (Oxford University Press, 1998) and Adam Jortner, No Place for Saints: Mobs and Mormons in Jacksonian America (John Hopkins University Press, 2021).

One could also point to race riots across the United States, as well as riots against Catholics, such as the deadly anti-Catholic riot in 1844. See Zachary M. Schrag, “Nativist Riots of 1844,” The Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia (2013), here.

When referring to pan-Protestantism, I mean a broad loose alliance of Protestant denominations that disagreed doctrinally, but saw each other as allies in a broader struggle against Catholicism, “heathenism,” and by the late 19th century, against “Mormonism.” The roots of this phenomenon are in the early British Empire, which became imbedded in the American society. I personally feel scholars have imposed to early the separation of church and state on the United States. While the United States allowed for religious pluralism, it was heavily based on broad Protestant definitions of morality and belief. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th century that a more rigid “wall” between church and state came into being. For British pan-Protestantism see Katherine Carte, Religion and the American Revolution: An Imperial History (University of North Carolina Press, 2021) and Linda Colley, Britons: Forging the Nation (Yale University Press, 1992).

He prayed for the builders of the tabernacle, for Brigham Young, his counselors (Heber C. Kimball and Richards himself), Patriarch John Smith, the Twelve Apostles, the various Priesthood quorums and missionaries serving missions, the Presiding Bishop Edward Hunter and his counselors, the Salt Lake Stake Presidency, those working on the public works, the Saints assisting the migration of new converts to the Salt Lake Valley, Saints abroad, and “all of thy people in these vallies of the mountains.” It is important to note at this time that the Relief Society remained unorganized, though women organizations existed outside the Church leadership structure. Local Relief Societies would begin forming at the direction of Brigham Young in 1854, with the reestablishment of a general Relief Society occurring in 1867. This is perhaps a part of why Richards neglected to reference the women of the Church specifically.

For more on the Relief Society see: Ed. Jill Mulvay Derr, The First Fifty Years of Relief Society: Key Documents in Latter-day Saint Women’s History (The Church Historian’s Press, 2016). The full book is free and available here at the Church Historian’s Press website. It is important to note that though in many ways Latter-day Saints were more “progressive” in regard to women, they had not yet reached a fullness of light and knowledge, being still bound by cultural traditions that bound women out of public leadership roles (see Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (The University of North Carolina Press, 1985). The current prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, President Dallin H. Oaks said, “We have not always been wise in using the great qualifications and powers of the daughters of God…We have work left to do, but we are a lot better off than we were even a decade ago.”

For the concept of ongoing restoration see the following

Gary E. Stevenson, “The Ongoing Restoration,” BYU Speeches (Aug. 20, 2019), here.

David A. Bednar, Instagram Post, July 9, 2023, here.

Elder LeGrand R. Curtis Jr., “The Ongoing Restoration,” Liahona (Apr. 2020), here.

Trente Toone, “Church historian and recorder takes a closer look at ‘all things’ in the ‘ongoing’ Restoration of the gospel at Church History Museum event,” Church News (Feb. 23, 2024), here.

For History of the Relief Society see:

Daughters in My Kingdom: The History and Work of the Relief Society (The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2011)

“Female Relief Society of Nauvoo,” Church History Topics, here.

An extensive archive of BYU published materials here.

Richards also asked that “may not the lawyers have power to stir up strife and contention, and lawsuits in our midst,” a common belief among Latter-day Saints who viewed lawyers as contention causers and trouble makers.

See 1 Kings 17-19; 2 Kings 1-2

See for example: Paul W. Reeves, Religion of a Different Color: Race and the Mormon Struggle for Whiteness (Oxford University Press, 2015)

It should be noted that some, in attempting to explain the Priesthood ban against African descended members of the Church ventured into creating sub-groupings within the family of God (though it should be noted that these never descended into the realm of “sub-human” categorizations of the Western world which at times depicted African peoples as outside the family of Adam). All of these speculations are rejected by the Church today.