This is the first of a four part series. I originally wrote this essay as an undergraduate and have decided to share it with my readers! I hope you enjoy!

The cages holding the group of survivors were small and confining. The sight, sound and smell of dysentery overwhelmed many of the captives as they sat huddled in their cages awaiting the dawn. The cages were a little over a yard high, three quarters of a yard long, and half a yard wide. For those accustomed to the respect and at times fear accorded to British citizens at the far reaches of the empire, their experience was humiliating and terrifying.1

Several days before, on September 15, 1840, during the heart of the First Opium War (September 1839-August 1842), they had watched as water flooded the cabins of the ship HMS Kite and dragged it under the waves of the harbor. The captain’s wife was near hysterical as she watched the ship go down with her little son. The terror of the shipwreck was only added to by the arrival of local Chinese fishermen, who instead of aiding, had bound them and taken them ashore. Dragged through the countryside till they reached Ningbo (Ningpo), China, a city renowned for its floating bridges and architecture. The survivors had been placed first in the local prison, and now in cages like wild animals. Yet, it was not just the cages that made the captivity so horrible. It was the hours spent on the daily parade through the city. As one sailor recorded, “I was once more exposed to the mercies of the mob; the soldiers, our guard, never making the slightest attempt to keep the people off. Fortunately for me I had had my hair cut close only a few days before we were wrecked, so that there was little or nothing to lay hold of.”2

This sailor, as well as a handful of other survivors of the Kite found Ningbo, China to be a city of nightmares. The sounds of harsh, angry voices in a foreign tongue, the wounds inflicted by the crowds, and the sheer brutality of their imprisonment embedded itself into their memories. They had watched as several of their comrades were beaten to death by a mob, while others died of dysentery trapped in their cages. How little did these unfortunate victims of the clash of empires realize that the community’s actions were in response to the intrusion of Britain upon China. It was a result of decades of opium smuggling by the British and the havoc that it had wrecked on Qing society. The brutality shown to these survivors was a manifestation of the frustration with foreigners felt by these Qing citizens.3 It was an outpouring of pent-up anger of a once powerful empire coming to grips with the changing tide. These realities were shrouded to the prisoners by the terror of the moment, the fear they experienced in the city imbedding itself into the narratives the survivors would tell upon their return to England. These narratives were also laced with ideas of cultural superiority and touched with racialized ideas. In a world of racialized imperialism, these ideas would not have been abnormal or foreign.

For the Chinese of Ningbo, they had won a minor victory. The British, who for years had slowly been humiliating the once great Middle Kingdom with an inundation of opium, had been brought to terms. The British had been forced to beg for the release of the captives and act subservient to the Qing. It was a victory, a momentary return to the respect once afforded the Qing Empire. Yet, the moment was to be short lived. As the British captives sailed away, the city returned to normal, the markets bustling. However, the terror the inhabitants of the city had meted out was soon to be returned with devilish delight by the British soldiers who marched into Ningbo a year later. The war changed not only the lives of the inhabitants of Ningbo, but the lives of every Qing subject for the rest of the century.

The First Opium War was devastating for China. It reduced the power of the Qing emperor and opened the nation to Westerners in a way previously unseen. This essay will sidestep the debates of the impact of the First Opium War on Great Britain and China. The Battle of Ningbo, though small and seemingly insignificant, captures the larger narrative of the war in its short bloody duration. But more than capturing the larger narrative of the First Opium War, the Battle of Ningbo was a turning point in history. The story of Ningbo is one of triumph and tragedy, the harbinger of future defeats and sorrows for China. It perfectly illustrates the imperial expansion of Great Britain during the 19th century, replete with acts of dehumanization and brutality against an Asian people. However, it also demonstrates the determination of Qing subjects and officials to resist British imperialism. Determination ultimately was unable to overcome sheer force and after this battle, the Qing forces became increasingly demoralized. It marked the beginning of the end of the Qing fight during the First Opium War and was the catalyst of Qing defeat.

Part 1: The British Storm

Prior to the events of the sinking of the Kite, the battle of Ningbo and the First Opium War, the Qianlong Emperor was facing crisis after crisis. The 19th century had seen the Qing empire racked with civil wars, declining markets, and increasing European intervention in Chinese life. Across the globe European powers, fueled with the benefits of the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions, were beginning to expand their influence into Asia and Africa. As the insatiable desire for empire and trade drove Europe’s expansion, these revolutions had an impact on Europeans' impressions of the Qing Empire. No longer were the impressions as flowery and awe inspiring as those hundreds of years prior when the first traders arrived in China. The status quo of trade between China and the West, which had been restricted to a few select ports, was tested and challenged, mostly by the British Empire, the global superpower.4

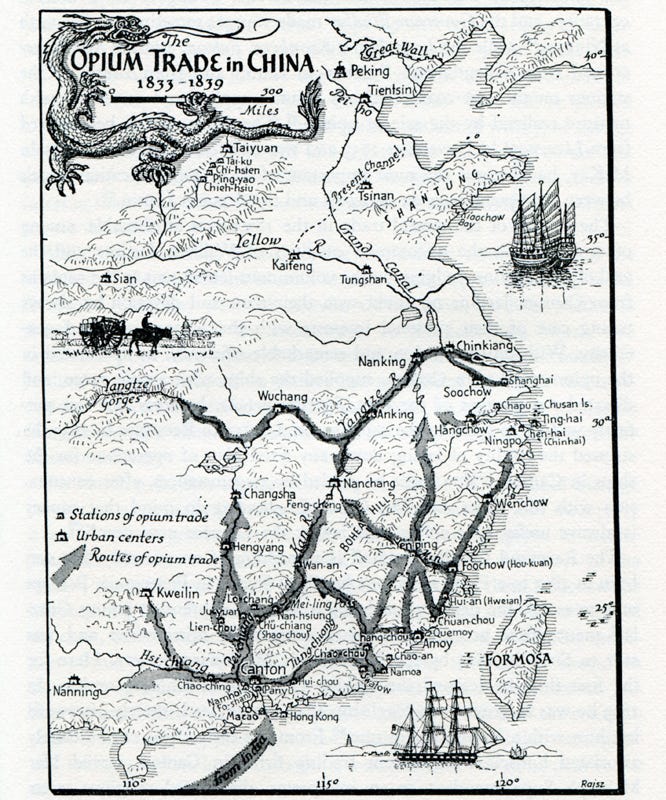

As the British government challenged the Qing rulers, a small drug was beginning to have a disastrous effect on China. As the silver trade declined in China, merchants sought an alternative to continue the trade of porcelain and silks. The solution was a narcotic produced in Indian and Afghan poppy fields and smuggled into China by British, American, and other foreigners. As tensions mounted between opium traders and the Qing officials, British East India company officers took steps to alienate the Qing government and push the two countries towards war. As one author noted, “Production was now to be increased as a deliberate policy, the aim being to sell the maximum possible quantity of opium to the Chinese, even if this meant a drop in price, in the hope that increased sales would compensate for the lower profit margin.”5

Qing officials, angered at the illegal drug trafficking and the rise of addiction in China, retaliated by shutting off the opium trade in Canton. This move was not done on a whim and came after decades of pleading with British government officials to control their merchants. With their backs against the wall, the Qing lashed out. The British East India Company reacted swiftly to the threat to its commerce and at the apparent opportunity to expand the commercial reach of its merchants. The British government in turn was brought into the war and began to supply troops to the help end it.

Soldiers began arriving from India and South Africa, many of whom were veterans of Britain’s wars of empire. The Qing army, though numerically superior, was woefully underprepared to fight against the British. The Qing navy was quickly destroyed, and thousands were killed in lopsided battles. By 1840, war was advancing across southern China as the British retaliated against the closure of ports to her precious drug. Despite it all, the Qing officials refused to concede.6

As Canton, Hong Kong and other cities fell to the British storm, the northern coastlines remained relatively quiet. However, Sir Henry Pottinger, one of the leading British commanders, planned to shatter that peace. In August of 1841 the British war machine advanced north along the coastline taking Dinghai.7 British military plans centered on forcing the emperor to accept British terms and expand British trade rights while maintaining low British casualties.8 This plan included a capture of the Grand Canal thereby cutting off the food supply of the capital. Ningbo was selected as the staging ground for this expedition and for the hopeful termination of the war.

Despite the relative peacefulness in the north half of the country, the Qing army had prepared for eventual attacks from the British. In the Ningbo area, the city Chen-Hai (Zhenhai) had been selected to withstand a British attack and deter attacks on Ningbo itself. Chen-Hai stood at the mouth of the Yongjiang River on a small rocky peninsula. Above the town a 200 foot rock with steep sides held the citadel that threatened any approaching British vessels.9 The fortress contained dozens of cannons, both outdated and modern, with which to withstand the invasion. Over 4,000 Chinese soldiers were stationed in the city for its defense and Governor Yuk’ien was placed in charge of the defense.10 Determined and ruthless, Yuk’ien prepared his men to fight to the death. They were to hold the fortifications erected in the city and along the river. As seen throughout most of the war, the Chinese stood ready and able to defend their homeland. They prepared for the assault using some European tactics, including the use of European firearms and cannons. D. McPherson, a British soldier, recalled numerous cannon positions and redoubts and also piles of logs driven into the riverbanks to prevent troops from landing. He also noted that the Qing had placed mines around the city. Confidence perhaps filled the hearts of many of the fresh recruits. They may have wondered how the British could ever penetrate the twenty-two-foot-high walls of the citadel.11 Others may have feared as rumors from the south told of the annihilation of Qing navies and battalions. The soldiers waited however, perhaps hoping that the British advance would halt or that the adoption of European tactics would forestall the coming storm. Both hopes proved useless as the British arrived in the harbor of Ningbo.

The morning of October 10, 1841, the British flotilla took up positions to begin bombarding the fortress. After the guns began to fire, 1,500 British troops were put ashore a few miles east of the river mouth near Chen-Hai.12 The troops had been divided into three columns, and as the Qing saw the British, “they cheered, and waved [the British] to approach, keeping up a constant though not a very effectual fire.”13 Charging ahead, the British drove straight into the Qing lines. The Qing were mostly new recruits and after some fierce fighting on the shore, they broke ranks and began to flee. The British veterans gave chase, while British cannons showered the city in hot lead and grapeshot, forcing the inexperienced Qing to abandon their cannons. British marines and seamen began scaling the cliffs and soon had possession of the citadel. The British soldiers followed up the hill and stormed the city. According to some reports only several British soldiers fell, in contrast with the hundreds of Qing defenders.14 This battle also exposed many Qing defenders to the brutality of the British army. A soldier on the battlefield, John Ouchterlony, later recorded, “Every effort was made by the general and his officers to stop the butchery, but the bugles had to sound the ‘cease firing’ long and often before the fury of our men could be restrained.”15

Throughout this first battle the Qing demonstrated tenacity and dedication in defending their homes as they charged the British line time and time again. However, no amount of courage and pluck could stop the roar of the British rifles and cannons as they tore into the poorly armed and trained Qing soldiers.16 It was not just the Qing soldiers who suffered. McPherson noted as he surveyed the town following the battle, “Here [in their temple] their hideous idols, shattered and broken by the shot, lay indiscriminately on the ground, with the mangled corpses of those who worshipped them. In one house in the city a poor woman was found with her leg shot off, and in another four little children were lying dead, the effects of a shell that had burst over them.” The soldier sadly added, “unfortunately, disasters of war do not fall upon the guilty or contending parties alone.”17 The stark and vivid imagery conjured by this soldier, portrays the suffering of Qing citizenry as the British made their advance inland. As with any war, the suffering went far beyond the combatant forces and military camps. One officer, who visited the city a year later noted, “It forcibly struck our whole party, that the people here seemed more frightened and timid than we elsewhere had been accustomed to see them. This, perhaps, is not to be wondered at, considering the frightful example which had been made of their once flourishing town, added to the awful slaughter which the Chinese troops sustained when it fell, which troops were principally, if not entirely, a species of militia; consequently the inhabitants of the place itself.”18 Yet, often this suffering was forgotten by the soldiers in the heat of the moment. One lieutenant recalled hearing many say, “They had had satisfaction out of the Chinese. It will be some time, I should think, before they come to time again. They never had met a drubbing before.”19

Following the loss of Chen-Hai, the British army began cutting off the Qing men’s hair to bring back as souvenirs to their girls in India and South Africa. They were eventually stopped by Sir Gough, one of the expedition’s commanding officers.20 The dehumanizing and humiliating tactics only further enraged the Qing people when they learned of the defeat. This illustrated another aspect of the First Opium War that would be repeated again and again. British cultural disdain and mockery of Qing tradition and actions were permitted by many officers and in some cases encouraged. Agents of empire, these soldiers transmitted ideas of Western supremacy and racial superiority in their narratives that they in turn would market to audiences at home in Britain. Perhaps done unknowingly, the cultural structure that encouraged these narratives were rampant not only in the lives of ordinary soldiers, but also among the elites of the British government and military.

To be continued…

W. Travis Hanes III and Frank Sanello, The Opium Wars: The Addiction of One Empire and the Corruption of Another (Naperville; Sourcebook Inc, 2002), 111.

John Lee Scott, Narrative of a Recent Imprisonment in China after the wreck of the Kite (London; W.H. Dalton, Cockspur Street, 1841), 42.

To be certain, without the demand, the British would not have imported. Similar critiques can be leveled against America today as drug addiction drives narcotic trafficking. Similarly, brutality by any culture should not be justified.

Harold M. Tanner, China: A History (Indianapolis; Hackett Publishing Company, 2009), 381.

Brian Inglis, The Opium War (London; Hodder and Stoughton, 1976), 75.

Tanner, China: A History, 381- 384.

P.C Kuo, A Critical Study of the First Anglo-Chinese War with Documents (Westport; Hyperion Press, 1935), 156-157.

Inglis, The Opium War, 151.

Peter Ward Fay, The Opium War: 1840-1842 (Chapel Hill; The University of North Carolina Press, 1975), 315.

Hanes and Sanello, The Opium Wars, 137-38.

D. McPherson, The War in China: Narrative of the Chinese Expedition (London; Saunders and Otley, 1843), 219-220, 226.

Kuo, A Critical Study of the First Anglo-Chinese War, 157; McPherson, The War in China, 222.

McPherson, The War in China, 223.

Fay, The Opium War, 315.

John Ouchterlony, The Chinese War (New York; Praeger Publishers, 1970), 190.

The Compilation Group, The Opium War (Honolulu; University Press of the Pacific, 2000), 67; Hanes and Sanello, The Opium Wars, 138-139.

McPherson, The War in China, 226-227.

Arthur Cunynghame, The Opium War: Being Recollections of Service in China (Philadelphia; G.B. Zieber & Co., 1845), 169.

Alexander Murray, Doings in China: Being the Personal Narrative of an Officer Engaged in the Late Chinese Expedition (London; Richard Bentley, 1843), 57.

McPherson, The War in China, 225; Jack Beeching, The Chinese Opium Wars (London; Hutchison & Co., 1975), 139.

Great write up. Many of my great-great-grandparents were stationed in Asia with the British Empire. I'm sure they saw and did some fairly awful things. I'll look forward to the other parts of this story.